Paralysis Tick

Ixodes holocyclus

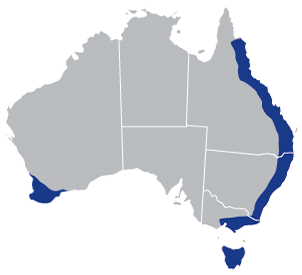

The Paralysis tick (Ixodes holocyclus), also known by other names such as the Seed/Grass, Wattle, or Hardback tick, is a hard tick found primarily in Eastern Australia. Similar to other Ixodes ticks such as the Blacklegged “Deer” tick (Ixodes scapularis), they do seem to be somewhat sensitive to climate conditions, requiring a relative humidity of at least 80% and are restricted to areas of moderate to high rainfall with good vegetation.

The Paralysis tick (Ixodes holocyclus), also known by other names such as the Seed/Grass, Wattle, or Hardback tick, is a hard tick found primarily in Eastern Australia. Similar to other Ixodes ticks such as the Blacklegged “Deer” tick (Ixodes scapularis), they do seem to be somewhat sensitive to climate conditions, requiring a relative humidity of at least 80% and are restricted to areas of moderate to high rainfall with good vegetation.

As are most other hard ticks, the Paralysis tick is a three-host tick: larvae, nymphs and adults feed on different hosts where larvae and nymphs prefers small to medium-sized animals and adults tend to feed on large-sized animals.

This tick species feeds on a broad range of mammals, birds and reptiles and (unfortunately) is known to frequently bites humans as well. Ixodes holocyclus is a known carrier of several pathogens of both medical and veterinary importance, including Tick Paralysis and Rickettsial Fever.

A species of hard bodied tick that may reach a length of up to 11 mm when engorged with a blood meal. Detailed examination is necessary for an accurate identification of this species.

Ixodes holocyclus are relatively small ticks, females being slightly larger than males. Larvae have three pairs of legs whereas nymphs and adults have four pairs. As members of the Ixodidae family, they have a sclerotised dorsal plate called a scutum which protects them from desiccation or damage. In males it covers the whole body, but in females, only partially covers the body. Ixodes holocyclus can easily be mistaken for other tick species such as Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes ricinus — however typically not when identified in Australia (not abroad).

Paralysis ticks have four life stages: egg, larva, nymph and adult and a three host life cycle. Ticks must take a blood meal in order to molt to the next life stage and produce eggs. The lifecycle is typically completed within three years, but can be shorter if climatic conditions are optimal and suitable hosts are abundant. Larvae or “seed/grass” ticks are tiny (0.5mm) and found mostly in autumn and winter.

After 3 different host feedings they then moult to the nymph stage which are about 1mm. Adults are most common from spring to midsummer. Usually only females bite people and other mammals. The bite is usually not notable but may rarely lead to paralysis, allergic reactions and tick typhus.

Mating usually occurs on the host and pheromones play an important role in finding a mate. Mating can last up to one week and once mated and fully engorged, an adult female will drop off a host onto the ground where she will seek conditions favorable for egg production. An engorged female will remain in this environment for 4-8 weeks before eggs are produced. Up to 3,000 eggs can be produced, after which the female dies and larvae hatch around six to eight weeks later.

Paralysis Tick Bites

While humans are certainly common hosts of the Paralysis tick, bandicoots, possums and echidnas are the most common wildlife which transmit paralysis ticks. Due to continuous exposure to the toxin, they have built up resistance over time and are usually immune to its effects.

Paralysis Tick bites typically initially cause local itchiness and a hard lump at the site of the bite with other more serious symptoms presenting themselves over number of days whilst the tick engorges itself. In some cases, this bite may even feel like a bee sting and can be painful. Over time, symptoms may include flu-like symptoms, rashes, an unsteady gait, weak limbs and partial face paralysis. Other problems associated with Paralysis Tick bites are allergic reactions ranging from mild itching and swelling to potentially life threatening anaphylactic shock.

Young children tend to be the most susceptible to problems caused by these ticks, as they may not be able to communicate they have been bitten and so ticks can be feeding on them for a number of days by which time their symptoms are quite advanced.

Medical Significance

Ixodes holocyclus is a carrier of Rickettsial Spotted Fever (also known as Queensland tick typhus), and tick paralysis. Some people have also experienced allergic reactions after coming in contact with both live and dead tick products. Having a tick simply walk over a person’s hand produces in some people an intense discomfort and itching. What particular components of the tick body cause these reactions is unknown, but it could be a water-soluble component that is excreted through the cuticular canals.

An association between tick bite reactions and mammalian meat allergy (Alpha-Gal Syndrome) in humans has also been reported. The induced allergy is unusual in that the onset of the allergic reaction, which ranges from mild stomach symptoms to life-threatening anaphylaxis (skin rashes, swollen tongue and serious drop in blood pressure), can occur up to 3 to 6 hours after eating mammalian meat (typically beef, lamb or pork) and often many months after the tick bite.

All mammals except humans and certain apes have a carbohydrate commonly known as alpha-gal (galactose-α-1,3-galactose) in their tissue fluids. When a tick feeds on the blood of a mammal (bandicoot, possum, cat, dog etc.) it takes alpha-gal into the tick’s digestive system. When the same tick attaches to the next host (e.g., a human) it transfers the alpha-gal to the tissues of that next host.

The immune system of some humans recognises alpha-gal as foreign and so produces antibodies against it. In this case the antibody produced is IgE, which is the type of antibody responsible for most allergic reactions. Thus the human is primed for a delayed allergic reaction to subsequent ingestion of mammalian meats (but not chicken or fish).

Alpha-gal allergy in a human can now be recognised through a blood test. The reaction to alpha-gal is distinct from any immediate allergic reaction to the tick itself, which is provoked by proteins in the tick’s saliva, not the carbohydrate alpha-gal. People who have such allergic reactions, however, may have a greater predisposition to also developing the allergy to mammalian meats over the next several months.

Veterinary Significance

Dogs and cats on the east coast of Australia commonly succumb to the tick paralysis caused by Ixodes holocyclus. A similar tick species, Ixodes cornuatus, commonly known as the Tasmanian Paralysis tick, appears to cause paralysis in Tasmania. The paralyzing toxin (or toxins) is produced in the salivary glands and injected as part of the feeding process.

The adult female Paralysis tick is usually attached for a minimum of 3 days before the very earliest signs are noticed although a very observant person might begin to notice a slight change in behavior after 48 hours of attachment (in a warm climate). Typically, however, a person would not notice obvious signs until at least the 4th day of attachment.

In colder weather the feeding process is slowed considerably and some animals may not show significant signs of paralysis for as long as two weeks. Furthermore, dogs rarely show significant signs until the adult female has engorged to a width of at least 4 mm (measured at the level of the spiracles; see photo of lateral view of Ixodes holocyclus).

If left untreated, the outcome is often (if not usually) fatal. The toxin or toxins paralyze muscle tissue; in particular: skeletal muscles (resulting in the overt paralysis the tick is named for), respiratory muscles (shallow breathing, inability to cough), laryngeal muscles (causes inhalation of food, water and vomit into the lungs), esophageal muscles (causes excessive drooling and regurgitation), and heart muscles (resulting in congestive heart failure).

After the tick is removed, the signs usually continue to worsen for up to 48 hours, though worsening is usually most pronounced in the first 12–24 hours after removal.