Castor Bean Tick

Ixodes ricinus

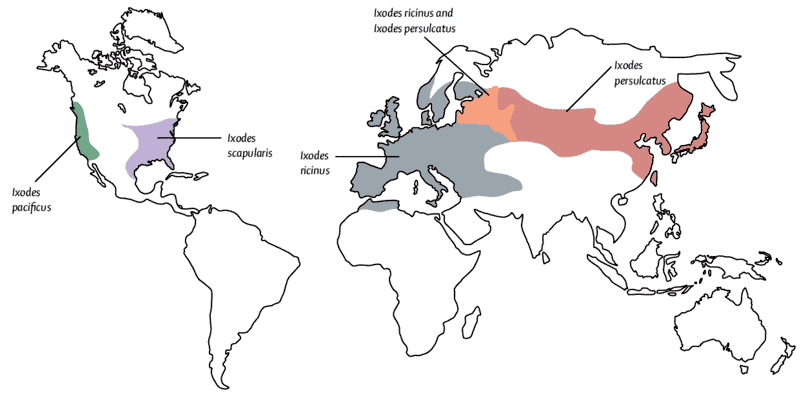

The Castor Bean tick (Ixodes ricinus), also known as the Sheep or Deer tick, is a hard tick having a wide indigenous geographical range, covering a the EU from Portugal to Russia and from North Africa to Scandinavia. They do seem to be somewhat sensitive to climate conditions, requiring a relative humidity of at least 80% and are restricted to areas of moderate to high rainfall with good vegetation.

Castor Bean ticks have been primarily observed across Europe in deciduous woodland and mixed forests, but can also be found in a range of habitats that support its blood hosts and a moist microclimate.

As are most other hard ticks, the Castor Bean tick is a three-host tick: larvae, nymphs and adults feed on different hosts where larvae and nymphs prefers small to medium-sized animals and adults tend to feed on large-sized animals. This tick species feeds on a broad range of mammals, birds and reptiles and (unfortunately) is known to frequently bites humans as well. Ixodes ricinus is a known carrier of a large variety of pathogens of both medical and veterinary importance, including tick-borne encephalitis virus and Lyme disease.

A species of hard bodied tick that may reach a length of up to 11 mm when engorged with a blood meal. Detailed examination is necessary for an accurate identification of this species.

Ixodes ricinus are relatively small ticks, females being slightly larger than males. Larvae have three pairs of legs whereas nymphs and adults have four pairs. As members of the Ixodidae family, they have a sclerotised dorsal plate called a scutum which protects them from desiccation or damage. In males it covers the whole body, but in females, only partially covers the body. Ixodes ricinus can be mistaken for other tick species such as Ixodes hexagonus and Ixodes persulcatus.

Castor Bean ticks have four life stages: egg, larva, nymph and adult and a three host life cycle. Ticks must take a blood meal in order to molt to the next life stage and produce eggs. The lifecycle is typically completed within three years, but can be shorter if climatic conditions are optimal and suitable hosts are abundant.

Mating usually occurs on the host and pheromones play an important role in finding a mate. Mating can last up to one week and once mated and fully engorged, an adult female will drop off a host onto the ground where she will seek conditions favorable for egg production. An engorged female will remain in this environment for 4-8 weeks before eggs are produced. Up to 2,000 eggs can be produced, after which the female dies and larvae hatch around eight weeks later.

Tick phenology varies throughout its distribution and can show a unimodal or bimodal pattern, reaching its maximum density in spring or autumn. Generally, Castor Bean ticks display a bimodal pattern of activity but this can vary from year to year at any given site. Local abundance depends on a variety of factors including habitat or host availability and varies between different countries.

Feeding Process & Host Preferences

Ixodes ricinus ticks quest for hosts using an ‘ambush’ technique whereby they climb to the tips of vegetation and wait for a host to brush pass. During questing, the tick loses moisture so has to climb back down the vegetation into the mat layer to rehydrate therefore the questing period is directly affected by temperature and humidity. Moving back into the mat layer reduces the probability of coming into contact with a host and uses up energy stores so is detrimental to tick survival.

Castor Bean ticks lack eyes, but possess a sensory organ called the “Hallers organ” which is used to detect changes within the environment such as temperature, carbon dioxide, humidity and vibrations, which can indicate the best times to quest and the presence of a host. Each stage attaches to a single host and feeds on blood for a period of days before detaching and then molting (larva/nymphs) or producing eggs.

Larvae do not move horizontally over a large distance so often remain aggregated within their environment whilst waiting for a host. Once a host is found, they can feed and molt to the nymphal stage and become dispersed within the environment. Prior to, and during the feeding process, the tick produces saliva which contains anti-coagulant, anti-inflammatory and anesthetic properties which aid in the feeding process and allow the tick to remain attached virtually undetected.

Ixodes ricinus ticks feed on a wide range of hosts including small rodents, passerines, larger mammals like hedgehogs, hares, squirrels, wild boar and deer with the juvenile stages feeding on smaller hosts such as wood mice; and adult stages feeding on larger hosts, such as cattle and deer. Larger hosts are important in maintaining tick populations, with populations tending to be lower in the absence of larger hosts. Movement of hosts can also affect population numbers or result in the establishment of foci in new areas. Ixodes ricinus ticks are also well known for biting humans.

Medical Significance

Ixodes ricinus is involved in the transmission of a large variety of pathogens of medical and veterinary importance including Lyme borreliosis, tick-borne encephalitis virus, Anaplasmosis, ehrlichiosis, Tularaemia, Rickettsia, Babesiosis, Louping Ill virus and Tribec virus.

Veterinary Significance

Louping Ill

This is a viral disease that attacks the central nervous system and is the most common and economically serious disease risk for sheep, causing death in animals that are naïve or unvaccinated. Affected sheep will initially develop a fever and lack appetite. Muscular trembling, unsteadiness, seizure and paralysis may then develop with death occurring in 5-60% of cases. In areas where Louping ill is endemic, the mortality rate is 5-10%. Young lambs acquire passive protection in colostrum, but as this wanes they become susceptible. Vaccination can play a role in protecting lambs and boosting colostral antibodies in ewes.

Tick-Borne Fever

Tick-borne fever is caused by the bacteria Anaplasma phagocytophilum and suppresses the immune system of the host animal. Infected individuals will have a sustained high temperature, anorexia and depression and, because of a suppressed immune system, are susceptible to other diseases (such as Louping ill and tick Pyaemia). Naïve in-lamb ewes are likely to abort and may develop severe metritis (inflammation of the uterus) if untreated and naïve rams may become infertile.

Tick Pyaemia

Young lambs (up to 12 weeks old) can be affected by Tick Pyaemia, which causes abscesses in the tendons, joints, muscles and brain and causes ‘crippled lambs’ with severe lameness, paralysis of the backend, ill thrift and death. Up to 30% of the lambs in a group can be affected and there is no treatment.

The Sheep tick is typically well known to those who have lived or live in the countryside or in the woods. These ticks are experiencing a period of revival due to the increasing integration between city and forest. It is not hard to spot it on low vegetation (grass, bushes, undergrowth) where it waits for a passing host. The period of increased possibility of aggression from this parasite runs from April/May to September/October.

Ixodes ricinus cover a wide geographic region including; Scandinavia, British Isles, central Europe, France, Spain, Italy, the Balkans, east Europe and North Africa. Distribution has changed in a number of countries in recent years, with Ixodes ricinus being found at higher altitude in Bosnia & Herzegovina and Czech Republic. These changes in distribution have been suggested to be a result of a combination of factors including climate change, changes in land use, changes in deer populations and changes in wild boar populations.

Modeling of data suggests that Ixodes ricinus will become distributed throughout Norway, Finland and Sweden by 2071-2100 and also that deciduous woodland may extend northward in Finland and Norway which will assist in the further spread of Ixodes ricinus.