Brown Dog Tick

Rhipicephalus sanguineus

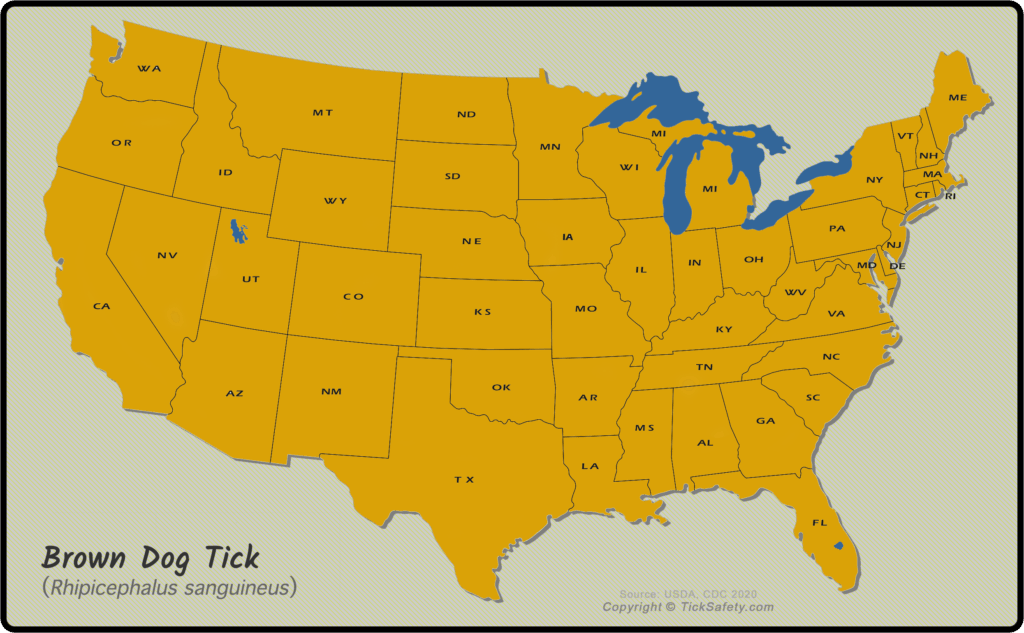

The Brown Dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus) has recently been identified as a carrier of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, in the southwestern U.S. and along the U.S-Mexico border. Brown dog ticks are found throughout the U.S. and the world. Dogs are the primary host for the Brown Dog tick for each of its life stages, although the tick may also bite humans or other mammals.

Quick Overview:

- Fairly uncommon to encounter on humans (typically only found on dogs)

- Human Diseases transmitted: Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (although rare)

- Veterinary Diseases transmitted: Canine Ehrlichiosis, Canine Babesiosis

- Can be found year-round

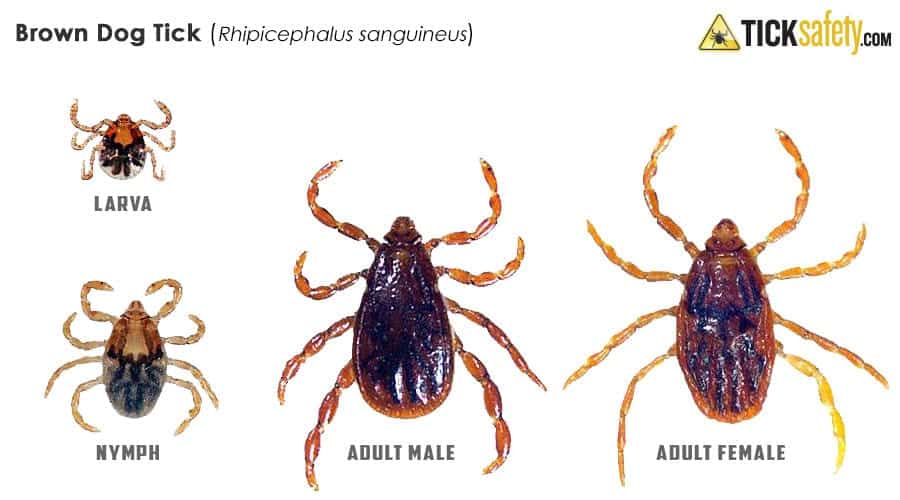

Frequently, when people report having a “tick infestation,” they often believe that they have several different types of ticks in their home or on their dogs – when in fact they are observing multiple life stages of the Brown Dog tick.

The different stages (larva, nymph, and adult) are progressively larger in size and once a blood meal is taken, tick size within a stage become larger and more variable. Many features used to identify the stages and sexes are difficult to see without a microscope. On male Brown Dog ticks, the scutum (dorsal shield) covers the entire dorsal surface, but only covers the anterior dorsal (area just behind the mouthparts) surface in females.

Males and females can be difficult to distinguish without examining them with magnification due to their lack of coloration, but males take only small blood meals while females take large meals and increase dramatically in size.

Nymphs are distinguishable from adults primarily by size, but this is unreliable and so these two stages need to be confirmed by microscopic examination, and usually by an expert.

The Brown Dog tick is a three-host tick; meaning each active stage (larva, nymph, and adult) feeds only once, then leaves the host to digest the blood meal and molt to the next stage or lay eggs. Mating of brown dog ticks occurs on the host following the stimulation of blood ingestion.

An adult female will feed on the host for about a week, then drop off the host and find a secluded place for egg incubation for about one to two weeks. Cracks and crevices in houses, garages and dog runs are ideal locations for this. She may start laying as soon as four days after she completes feeding and drops off the host, and can continue to lay for 15 to 18 days. As she lays the eggs, she passes them over her porose areas (specialized areas on the back of the basis capituli) to coat them in secretions that protect the eggs from desiccation.

A fully blood-fed female brown dog tick can lay over 7,000 eggs, with 4,000 on average. The number of eggs laid depends on the size of the tick and the amount of blood she ingested. The female dies after she finishes laying her eggs. The larvae hatch 6 to 23 days later, and begin to quest, or look for a host. The host seeking activity, which occurs in all the active stages, results in increased movement of ticks towards a dog, thus owners often see ticks drawn out into the open on furniture, baseboards, carpeting and dog bedding.

Larvae feed for 5 to 15 days, drop from the dog, then take about one to two weeks to develop into nymphs. The nymphs then find and attach to another host (possibly the same dog), feed for 3 to 13 days, fall from the dog and take about two weeks to develop into adults. As adults, both males and females will attach to hosts and feed, although the males feed only for short periods.

The length of time that each life stage feed, as well as the time required for development and molting, are both temperature dependent. Feeding and development times are generally faster at warmer temperatures.

Survival is generally higher at cooler temperatures and higher relative humidity, but these ticks are tolerant of a wide range of conditions. Although ticks are visible while looking for a host and feeding, they are not easily observed while digesting their blood meals, molting, or laying eggs, due to their cryptic behavior. This can lead to the apparent disappearance and then re-appearance of ticks in a residential infestation.

The overall development from egg to egg-laying female can be completed in just over two months, but frequently it will take longer if there are few hosts available or under cooler temperatures. Ticks are notoriously long-lived and can survive as long as three to five months in each stage without feeding. On average, two generations may occur per year, but up to four generations per year have been documented in countries in tropical regions. In Florida, the cycle can occur year-round both inside residences and in outdoor kennels and dog runs.

The Brown Dog tick has been reported to transmit the bacterial agent Ehrilichia canis, responsible for Canine Monocytic Ehrlichiosis and E. ewingii in dogs, and E. chaffeensis, the pathogen responsible for causing Human Ehrlichiosis. The Brown Dog tick has also been reported to transmit the bacterium Rickettsia ricksettsii, causing Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever in humans – especially in the southwestern US and Mexico. Other diseases commonly reported to be carried by the Brown Dog tick include Anaplasmosis and Babsesia vanis vogeli (in dogs).

Medical Importance

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF), caused by Rickettsia rickettsii, is a severe tick-borne disease in humans. While the Brown Dog tick is a potential vector of RMSF, it is far more commonly transmitted by the American Dog and Rocky Mountain Wood ticks. This pathogen was reported to be transmitted by Brown Dog ticks in Arizona and California, but transmission of RMSF by Brown Dog ticks has not been reported in any other states. Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever has been considered an epidemiological emergency in Mexico and the case-fatality rates can be high without prompt and correct treatment. The symptoms of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever tend to include a sudden onset fever, significant discomfort, rash, and headache.

In parts of Europe, Asia and Africa, Rhipicephalus sanguineus is also a vector of Rickettsia conorii. This is a sub-species of the bacteria that causes RMSF, and is the primary agent for the European version of RMSF, Mediterranean Spotted Fever and certain variations of Tick Typhus. Rickettsia conorii can be transmitted from a female tick to her offspring and transmitted between infected and uninfected ticks when they are feeding simultaneously on same host. Rhipicephalus sanguineus has NOT been shown to transmit the bacterium that causes Lyme disease.

Veterinary Importance

With populations of Brown Dog ticks potentially reaching dramatic levels in homes and kennels, this tick species is of particular importance to canines. The Brown Dog tick is a vector of several pathogens causing canine illnesses including canine Ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia canis) and canine Babesiosis (Babesia canis) in the United States. Symptoms of canine Ehrlichiosis may include lameness, depression, weight loss, anorexia, and fever; for Babesiosis, symptoms may include fever, anorexia and anemia.

In the southern United States, Brown Dog ticks may live in grass or bushes around homes, dog houses, or kennels. Brown Dog ticks are the species that is most often found in homes. As a result, Brown Dog tick populations can be found throughout the world, including areas with frigidly cold outdoor temperatures.

In the southern United States, Brown Dog ticks may live in grass or bushes around homes, dog houses, or kennels. Brown Dog ticks are the species that is most often found in homes. As a result, Brown Dog tick populations can be found throughout the world, including areas with frigidly cold outdoor temperatures.

The Brown Dog tick is found worldwide and is considered the most widespread tick species in the world. It is more common in warmer climates and in the United States, is present throughout Florida year-round. Brown Dog ticks are commonly found on dogs, in kennels and houses, and occasionally on wildlife.

The Brown Dog tick or “Kennel Tick” is found almost worldwide and throughout the United States. The tick is more abundant in the southern states and can be the most predominant tick on dogs in many areas. Domestic dogs are the principal host for all three stages of the tick. Adult ticks feed mainly inside the ears of the dog, in the axillae (i.e., “armpit”), head and neck, and between the toes, while the immature stages feed almost anywhere, particularly along the neck and back, but also legs, chest, and belly.

People may be attacked and there have been increasing reports of this tick feeding on humans. This tick is closely associated with yards, homes, kennels and small animal hospitals where dogs are present, particularly in pet bedding areas.

Brown Dog ticks may be observed crawling around baseboards, up walls or other vertical surfaces of infested homes seeking protected areas, such as cracks, crevices, spaces between walls or wallpaper, to molt or lay eggs. The brown dog tick can complete its life cycle completely indoors and in the North, this tick is found nearly exclusively indoors in homes or kennels.