Blacklegged "Deer" Tick

Ixodes scapularis

The Blacklegged “Deer” tick is a notorious biting arachnid named for its dark legs. Blacklegged ticks are sometimes called “Deer” ticks because their preferred adult host is the white-tailed deer. In the Midwest, blacklegged ticks are called the “Bear” ticks. Interestingly enough, their number one preferred host? White-footed mice!

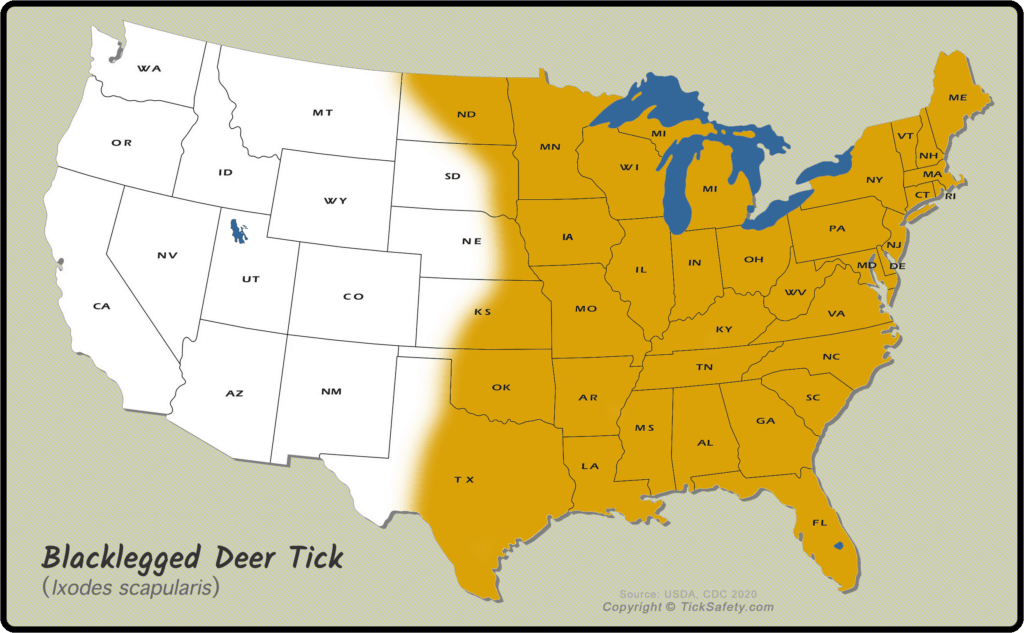

Deer ticks are found primarily in the northeastern, mid-Atlantic, southeastern, and northern central United States but extend into Mexico. This tick is of significant medical and veterinary importance because of its ability to transmit Lyme disease, Anaplasmosis, human Babesiosis, Powassan virus, and more.

Quick Overview:

- Commonly found in deciduous forests and shrubs bordering forests.

- Not typically found in open fields or in grassy areas.

- Diseases transmitted: Lyme disease, Babesiosis, Anaplasmosis, Ehrlichiosis, and Powassan Virus.

- Adult male ticks are not known for transmitting infections.

- Deer ticks are MOST active in the late Fall and early Winter months, and are typically far less active during hot summer months.

- Females typically lay their eggs (~2000 or so) in late May. Eggs then hatch in late summer.

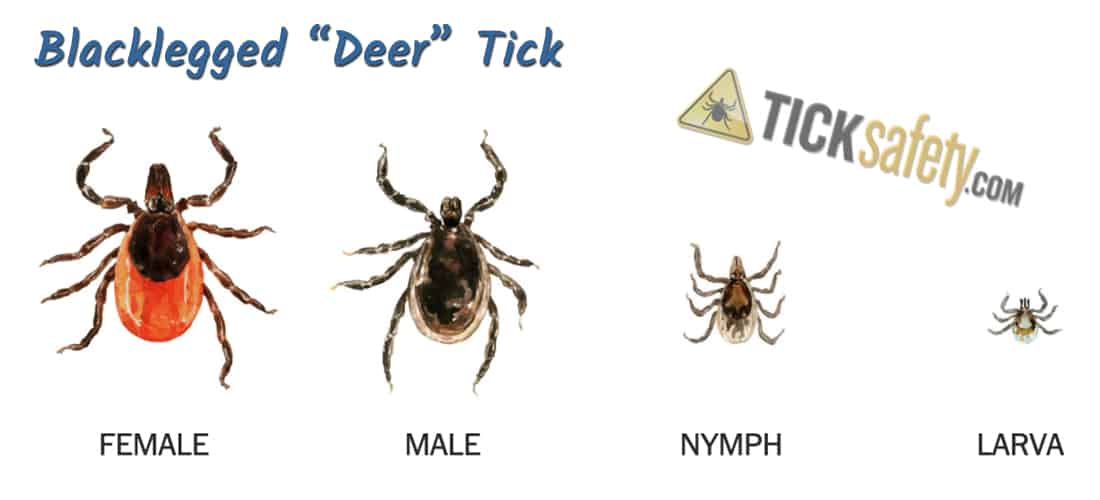

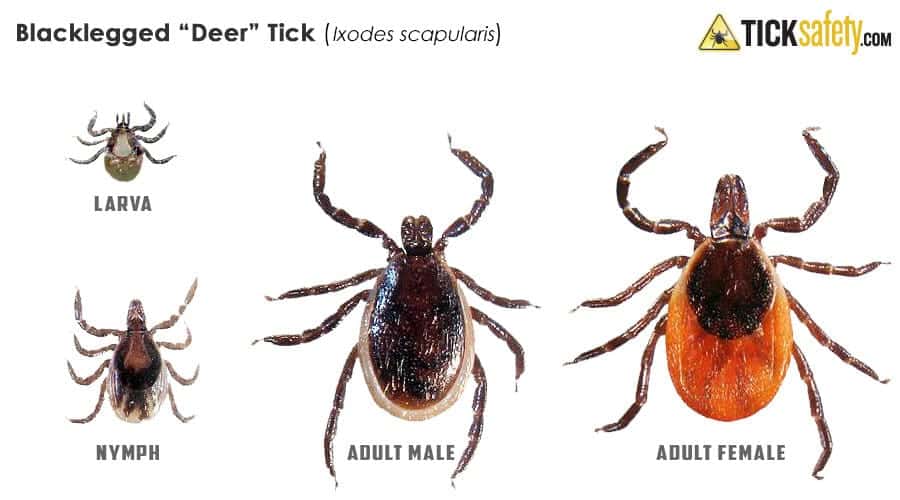

Unfed female Eastern blacklegged ticks, also known as deer ticks, are easily distinguished from other ticks by the orange-red body surrounding the black scutum. Males do not feed. A type of hard tick, deer tick populations tend to be higher in elevation, in wooded and grassy areas where the animals they feed on live and roam, particularly their reproductive host, the white-tailed deer.

Adult deer ticks have no white markings on the dorsal area nor do they have eyes or festoons. They are about 3 mm and dark brown to black in color. Adults exhibit sexual dimorphism. Females typically are an orange to red color behind the scutum.

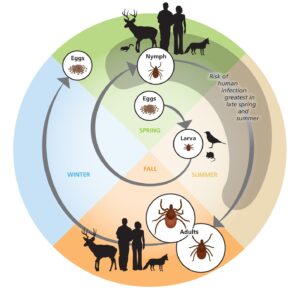

Ixodes scapularis is a three-host tick; each mobile stage feeds on a different host animal. In June and July, eggs deposited earlier in the spring hatch into tiny six-legged larvae.

Ixodes scapularis is a three-host tick; each mobile stage feeds on a different host animal. In June and July, eggs deposited earlier in the spring hatch into tiny six-legged larvae.

Peak larval activity occurs in August, when larvae attach and feed on a wide range of mammals and birds, primarily on white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus).

After feeding for three to five days, engorged larvae drop from the host to the ground where they overwinter. In May, larvae molt into nymphs, which feed on a number of hosts for three to four days. In a similar manner, engorged nymphs detach and drop to the forest floor where they molt into the adult stage, which becomes active in October.

Adult ticks remain active through the winter on days when the ground and ambient temperatures are above freezing. Adult female ticks feed for five to seven days while the male tick feeds only sparingly, if at all.

Adult ticks feed on large mammals, primarily upon white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). Beginning in May, engorged adult females typically lay between 1000 to 3000 eggs on the forest floor at the site where they detached from their hosts.

Mortality rates for ticks are high. Tick death is caused by density-dependent factors such as parasites, pathogens, and predators, all of which appear to have little impact on tick populations. Density-independent factors causing tick mortality include a range of adverse climatic and microclimate conditions.

Temperature and humidity have the greatest overall impact on tick survival. Due to their low probability of finding a host, starvation is a major mortality factor of ticks. Host immunity and grooming activity may affect mortality.

Feeding and Blood Meals

Blacklegged Deer ticks feed on blood by inserting their mouth parts into the skin of a host animal such as a mouse, dog, bird, or even human.

They are relatively slow feeders and will usually feed for 3-5 days at a time. In order to spread disease to a human or animal, first a tick needs to be infected with the pathogen and it needs to be attached and feeding for a certain amount of time.

If the tick is infected, on average it must be attached and feeding for 24-48 hours before it transmits Lyme disease. This timeframe is the average amount of time needed to transmit the Lyme spirochete; however, there have been a number of studies that have presented different findings.

The two most recent and largest studies done in the U.S. (2011 & 2017) presented two very different findings.

The first concluded that Lyme could be transmitted in as little as 16 hours, while the later study’s findings showed that a tick must be attached and feeding for “at least 48 hours or more” to transmit Lyme.

The bottom line is that the more time a tick is attached and feeding, the greater likelihood of disease transmission. On average, about 1 in 3 adult Blacklegged ticks and 1 in 5 Blacklegged Deer tick nymphs are infected with the bacteria that causes Lyme disease.

Less common tick-borne diseases, such as anaplasmosis, can be transmitted after just 24 hour; Babesiosis, after 36 hour of feeding.

Medical Importance

The Blacklegged “Deer” tick, Ixodes scapularis, is an important vector of the Lyme Disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, as well as several other agents that cause Human Babesiosis, Babesia microti, as well as Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis (HGE) and several more tick-borne illnesses.

A significant feature in the transmission dynamics of Borrelia burgdorferi — Lyme disease — is the importance of the nymphal stage’s activity preceding that of the larvae which allows for an efficient transmission cycle.

Before and during larval tick feeding, the naturally infected nymphs transmit Borrelia burgdorferi to reservoir hosts. The newly hatched spirochete-free larvae acquire the bacteria from the reservoir host and retain infection through the molting process.

In the springtime, nymphs derived from infected larvae transmit infection to susceptible animals, which will serve as hosts for larvae later in the summer.

Human exposure to Blacklegged Deer ticks is greatest during the summer months when high nymphal Ixodes scapularis activity and human outdoor activity coincide. Their small size, their vastly greater abundance over the adult stages and the difficulty in recognizing their bites tends to make nymphs the most important stage to consider for reducing disease risk.

Veterinary Importance

Most commonly encountered in dogs, Lyme Disease is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria. Lyme disease is transmitted by the Blacklegged Deer tick and the Western Blacklegged Deer tick. Lyme disease has been found throughout the United States and Canada, but infections are most frequently diagnosed in the northeastern, mid-Atlantic and north-central states, as well as in California.

More serious complications include damage to the kidney, and rarely heart or nervous system disease symptoms may come and go and can mimic other health conditions. Cases vary from mild to severe with severe cases sometimes resulting in kidney failure and death.

Canine Anaplasmosis is caused by Anaplasma species of bacteria, specifically Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Anaplasma platys. Both forms of canine anaplasmosis are found throughout the United States and Canada. Areas where canine anaplasmosis is more common include the northeastern, mid-Atlantic and north-central states, as well as California.

Anaplasma platys, specifically, is more common in Gulf Coast and southwestern states Anaplasma phagocytophilum is transmitted by the deer tick and the western black-legged tick. These are the same ticks that transmit Lyme disease which increases the risk of co-infection with multiple tick-borne diseases.

Blacklegged Deer ticks live in wooded, brushy areas that provide food and cover for white-footed mice, deer and other mammals. This habitat also provides the humidity ticks need to survive.

Exposure to ticks may be greatest in the woods (especially along trails) and the fringe area between the woods and border. Rarely, blacklegged ticks may be found in more open areas (such as yards) that are near wooded habitat so it is important to be on the lookout for ticks when in or near wooded areas.

Blacklegged Deer ticks search for a host from the tips of low-lying vegetation and shrubs, not from trees. Generally, ticks attach to a person or animal near ground level. In fact, they rarely ever climb trees, or go higher than 3 to 4 feet up. They do not fall out of trees.

Blacklegged Deer ticks also crawl; they do not jump or fly. They grab onto people or animals that brush against vegetation, and then they crawl upwards to find a place to bite. This action is called “questing.”

These ticks are primarily distributed in the Northeastern and Upper Midwestern regions of the United States.

Ixodes scapularis is found along the east coast of the United States. Florida westward into central Texas forms the lower boundary, although there are reports from Mexico. The upper boundary is located in Maine westward to Minnesota and Iowa.

The distribution of Ixodes scapularis is linked to the distribution and abundance of its primary reproductive host, white-tailed deer. Only deer or some other large mammal appears capable of supporting high populations of ticks. In the northeastern United States, much of the landscape has been altered.

Forests were cleared for farming, but were abandoned in the late 1800s and 1900s causing succession of the fields to second-growth forests. These second-growth forests created “edge” habitats which provided appropriate habitat for deer resulting in increased populations and thus, may have increased populations of the blacklegged tick.

Over the last two decades, the distribution of blacklegged ticks has expanded. They are now found throughout the eastern U.S., large areas in the north and central U.S., and the South.

The northern distributions of the blacklegged tick are continuing to spread in all directions from two major endemic areas in the Northeast and Upper Midwest. It’s important to note that adult ticks will search for a host any time when temperatures are above freezing, including winter.

Blacklegged ticks are found in a wide variety of habitat that are suitable for birds, large and small mammals such as mice, deer, squirrel, coyotes and livestock. All life stages can bite humans, but nymphs and adult females are most commonly found on people who are in contact with grass, brush, leaves, logs or pets that have been roaming the outdoors.

Blacklegged Deer ticks prefer to hide in grass and shrubs while waiting for a passing host. They prefer vegetation located in transitional areas such as where forest meets field, mowed lawn meets un-mowed fence line, or a foot trail through high grass or forest as these areas are where most animals travel sometime during each 24-hour period.

The other habitat most likely to harbor blacklegged ticks is the den, nest, or nesting area of its host such as that of skunks, raccoons, opossums, but especially the white-footed mouse. The white-footed mouse prefers woody or brushy areas. It nests in any place that gives shelter such as below ground, in stumps, logs, old bird or squirrel nests, woodpiles, buildings, etc.

During the winter, adult ticks feed primarily on the blood of white-tailed deer. In the spring, a female tick will drop off its host and will deposit about 3,000 eggs. Nymphs, or baby ticks, feed on mice, squirrels, raccoons, skunks, dogs, humans and birds.

A favorite feeding area for these ticks on humans is at the back of the neck, at the base of the skull; long hair makes detection more difficult. However, the ticks will usually crawl about for up to 4 hours or so before they attach. Then, a tick has to be attached for a period of 6-8 hours before a successful transmission can take place.