Asian Longhorned Tick

Haemaphysalis longicornis

The Asian Longhorned Tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis) is widely known as an invasive species in New Zealand and Australia (known there as a Bush tick), and has now made an appearance in the US.

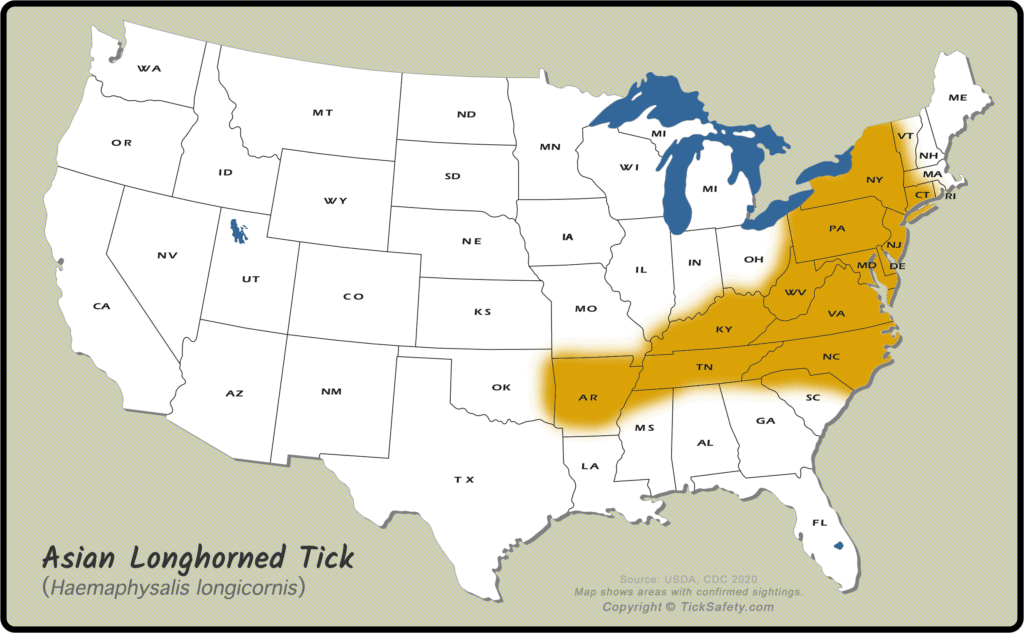

Although believed to have been in the US since 2010, it has only recently been “rediscovered” in 2017 on a farm in New Jersey. Since then, there have been additional confirmed sightings in West Virginia, Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, Ohio and Arkansas.

NOTICE: This tick is very easily confused with other ticks such as the American Dog tick and Lone Star tick. Identification by a professional or acarologist may be required for positive confirmation.

Asian Longhorned ticks are difficult to identify by non-experts. Given the importance of this new invasive species, if suspected Asian longhorned ticks are found in Florida, a sample should be sent in to Tick Safety for proper identification.

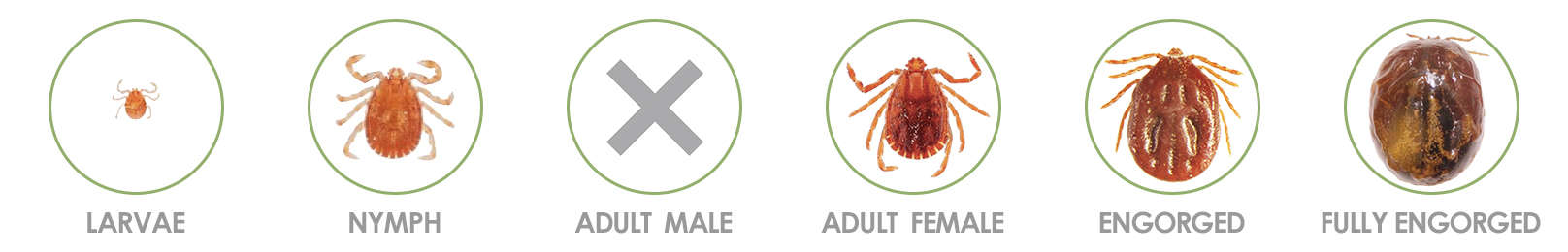

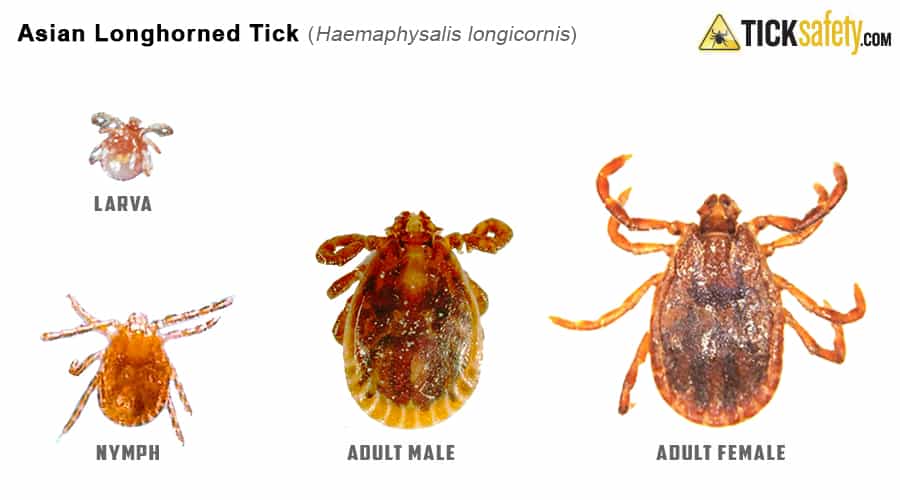

Larvae of Asian Longhorned Ticks have three pairs of legs with a body size of approximately 0.58 to 0.62 mm in length and 0.47 to 0.51 mm in width. The scutum (dorsal shield) of the larva is approximately 1.5 times as wide as it is long.

As with nearly all hard-bodied ticks, both nymphs and adults have eight legs. The presence of genital pores on adult females makes them distinguishable from the adult males and nymphs, where it is absent.

An un-engorged (prior to a blood meal) nymph is about 1.76 mm in length and 1 mm in width. The scutum of the nymph is approximately 1.25 times as wide as long, and its outline is broadly rounded. Females and males are reddish-yellow in color, but have different body sizes.

Females are 2.7 to 3.4 mm in length and 1.4 to 2 mm in width, while the smaller males are approximately 2.51 mm in length and 1.65 mm in width.

The scutum of females is smaller than that of males, covers only the anterior dorsal surface, and has an angular margin that becomes more obvious during blood feeding. The scutum on males covers the entire dorsal surface.

The Asian Longhorned tick is a three-host tick; meaning that after taking a blood meal, each active stage (larva, nymph, and adult) will leave the host to digest the blood meal, and develop and molt into the next stage, or if an adult female will lay eggs and die.

The engorged (fully blood-fed) female can produce up to 2,000 eggs over 2 to 3 weeks. The larvae hatch about 25 days after oviposition when held at 77°F.

These newly-hatched larvae immediately search for a host. After locating and attaching to a host, they feed for 3 to 9 days. Once larvae are engorged, they drop from the host and digest the blood meal before molting into nymphs, a period that may take up to two weeks.

Nymphs then locate and attach to a new host, feed for 3 to 8 days, and fall from the second host, where they take about 17 days to digest their blood meal and develop into adults. After finding a suitable host, adults may feed for 7 to 14 days before dropping from this third host.

The Asian Longhorned tick can compete its life cycle in six months, but typically one generation occurs per year, with most immature ticks entering diapause (dormancy) during winter and other cold periods.

The cues for ticks to enter diapause are both abiotic such as temperature, humidity, and photoperiod, and biotic such as nutrition. For nymphs, photoperiod and temperature are the only cues to induce diapause due to their resistance to dehydration.

The reproduction of Asian Longhorned ticks is unusual among tick species. They can produce offspring by both sexual reproduction (offspring that develop from eggs fertilized by a male) and parthenogenetic reproduction (offspring that develop from unfertilized eggs, from an unmated female).

Males are usually uncommon in invasive populations, such as the populations in Australia and New Zealand, and this appears to be the situation in the U.S. populations, although still unconfirmed.

The ability of female Asian Longhorned ticks to produce offspring in the absence of males could be the reason that this tick has spread rapidly and reached high abundances in Australia and New Zealand.

The annual pattern of Asian Longhorned tick populations is dependent on temperature, humidity, day length, and host availability. Temperature and day length are the major factors determining the time to complete each stage.

At temperatures ranging from 12 to 30°C, it takes 17 to 100 days for larvae to hatch, 11 to 45 days for blood fed larvae to molt into nymphs, and 13 to 63 days for blood fed nymphs to molt into adults.

Generally, the developmental rate increases as temperature increases, but slows as the temperature reaches the upper developmental threshold, which is near 104°F.

Ticks with larger body sizes may need longer periods to feed and develop (the adults feed for a longer time than the larvae). Also, the feeding period is extended when a larger number of ticks are present on same host.

Dehydration is the most limiting factor for tick survival because the ticks spend approximately 90% of their life off hosts in potentially desiccating environments. Unfed Asian longhorned ticks tend to lose water more rapidly than engorged ticks of the same species.

However, they have the ability to withstand dehydration. For unfed ticks, nymphs have the greatest resistance to dehydration, followed by larvae and adults. While for engorged individuals, adults have the greatest resistance to dehydration followed by nymphs and larvae.

Medical + Veterinary Importance

Pathogens of human and veterinary medical importance that has clearly been shown capable to transmit or repeatedly found infected with, and the associated parts of the world, include:

- Sheep Theileriosis (veterinary)

- Canine Babesiosis (veterinary)

- Babesiosis (veterinary)

- Anaplasmosis (veterinary)

- Ehrlichiosis (veterinary)

- SFTSV (human + veterinary)

- JSF (human)

- Powassan (human)

- HYSV (human)

The Asian Longhorn tick is a confirmed transmitter of bovine theileriosis and parasites that cause babesiosis infection in animals. Bovine theileriosis can reduce dairy production on cattle farms and occasionally kill calves.

The ticks themselves can also cause anemia in sheep and cattle when densities are high.

In Asia, field-collected Longhorned ticks can harbor pathogens that are also present, or very closely related to those found in the US. These include Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Babesia, and Powassan virus.

The capacity of this tick to act as a vector for these pathogens to humans has not been studied enough to make a definitive determination as to whether or not the tick is considered a viable transmission vector.

This species is also considered a possible vector for Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus (SFTSV) in China, an emerging infectious disease with a reported human mortality rate of up to 12%.

Important Note: As of July 2020, NONE of the Longhorned ticks collected in the U.S. have tested positive for any pathogens that affect humans.

Several ticks collected in southern Virginia in 2017, and again in 2021, have tested positive for or Theileria orientalis, a tick-borne disease that causes anemia and even sometimes death in cattle.

There are also a few pathogens that have been recovered from collected Longhorned ticks, but only rarely, such as Anaplasma ovis, Anaplasma marginale, Anaplasma platys, Ehrlichia ewingii, Ehrlichia canis, Bartonella sp., Rickettsia sibirica, Orientia tsutsugamushi, TBEV and Hepatozoon canis.

While not much is known about this species of tick and how it behaves in the U.S., this three-host tick tends to prefer livestock such as cattle, sheep and horses, however has been known to also bite humans, especially those tending livestock.

While not much is known about this species of tick and how it behaves in the U.S., this three-host tick tends to prefer livestock such as cattle, sheep and horses, however has been known to also bite humans, especially those tending livestock.

As larvae and nymphs, as with many ticks, Longhorned ticks tend to prefer birds and small mammals such as white-footed mice.

Longhorned ticks are most commonly found in and around the habitats of white-footed mice as well as livestock, Longhorned ticks are predominantly found in meadows and surrounding grassy areas and pastures located near forests.

While the East Asian Longhorn Tick is naturally endemic to Asia (China & Japan primarily), it is also widely known as an invasive species in New Zealand and Australia.

It has now also made an appearance in the U.S., and although they are believed to have been in the U.S. since around 2010, it has only recently been “rediscovered” in 2017 on a farm in New Jersey. Since then, there have been additional confirmed sightings in West Virginia, Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina and Arkansas.

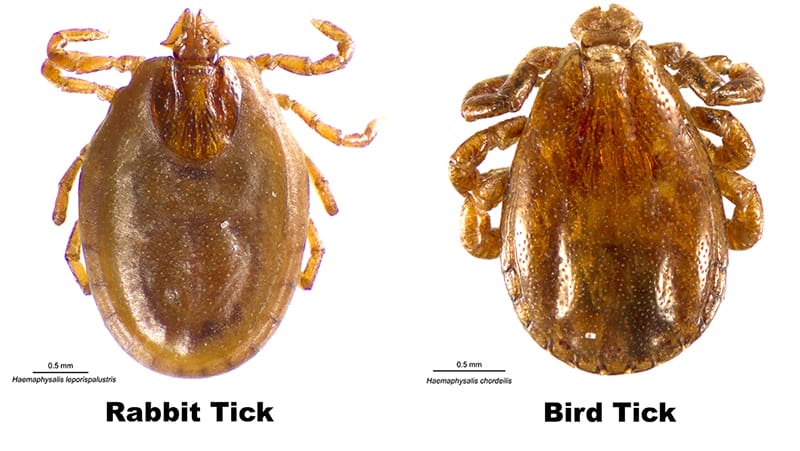

The East Asian Longhorned Tick is often and easily confused with two other ticks commonly found in the United States: the Rabbit Tick (Haemaphysalis leporispalustris) and Bird Tick (Haemaphysalis chordeilis). Both are found distributed across the country.